helicobacter pylori (or h.Pylori to its pals)

What is it?

H. Pylori was only discovered in 1984 so it’s pretty young in the microbial world. We’ve come up with a quick summary of the key bits we do know about.

We know that it’s a type of bacteria, it likes to live in the mucus lining of your stomach (the lower part of it) and it causes inflammation. It is thought to be prevalent in over 50% of the population and can stay there for life if untreated (pretty stubborn, huh?!). It is thought to affect many areas of the body from gut health to skin.

What does it do?

An H. Pylori infection is a bacterial infection of the stomach, where the bacteria sets up home in the mucus layer of your stomach. The majority of people with an H. Pylori infection don’t experience any symptoms – it all depends what virulence factors are present (they dictate how it colonises and the severity of infection).

It can weaken the mucus and expose the stomach lining causing inflammation and for some, stomach or duodenal ulcers. Common symptoms of an H. Pylori infection include abdominal pain, persistent indigestion, bloating, belching and nausea. It can be treated but requires medical intervention and proper diagnosis (Google isn’t going to give you the answer!). Ulcers are associated with indigestion but due to the common nature of indigestion, it doesn’t mean all ulcers cause indigestion and all those with indigestion have ulcers.

Although the true effect of H. Pylori is still unknown there is some research to suggest it may cause peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer, the reality is we just don’t know enough.

There’s also some evidence to suggest that H. Pylori may be associated with skin conditions, such as rosacea and psoriasis – but much more research is needed for a conclusive link to be drawn.

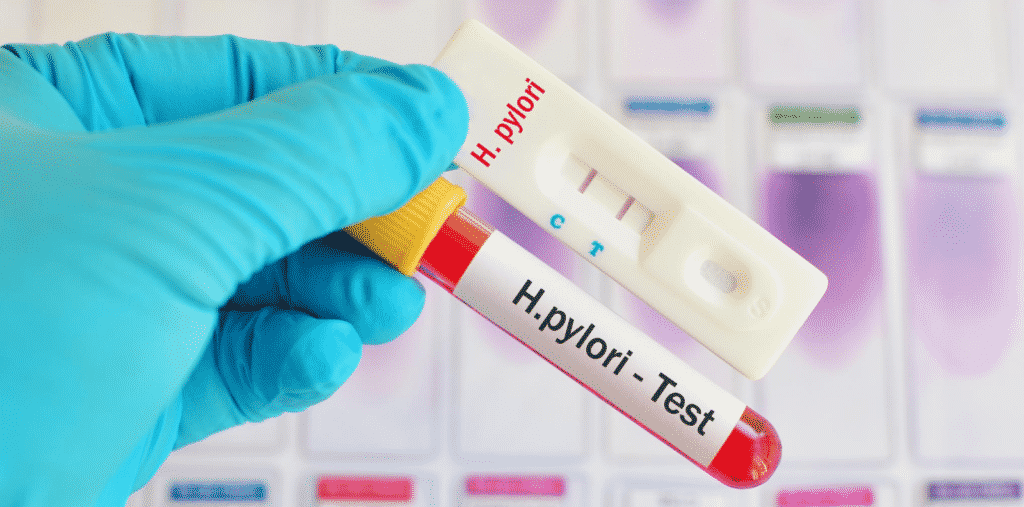

How is it diagnosed?

H. Pylori can be diagnosed via blood test, breath test, stool tests or while having an endoscopy (where a biopsy is taken). As with all tests, some are more accurate than others and can be unreliable if certain medications have been taken.

Treatment

H. Pylori can be treated. Treatment is with medication, including antibiotics. However, with the rise of antibiotic resistance, eradication of H. Pylori in the population is unlikely.

If you are taking antibiotics for treatment of H.Pylori, it is important that you look after your gut microbes too. Head on over to our gut tips page for more (and remember that if you take a probiotic, it needs to be taken well away from antibiotics).

Future

With advances in testing and more understanding of this complex bacteria, the future may hold some useful information as to its role in the development of many different conditions and diseases and how to manage overall gut health while being treated.

References

El-Khalawany M, Mahmoud A, Mosbeh AS, A B D Alsalam F, Ghonaim N, Abou-Bakr A. Role of Helicobacter pylori in common rosacea subtypes: a genotypic comparative study of Egyptian patients. J Dermatol. 2012;39:989–995

Gao, W., Cheng, H., Hu, F., Li, J., Wang, L., Yang, G., Xu, L., & Zheng, X. (2010). The evolution of Helicobacter pylori antibiotics resistance over 10 years in Beijing, China. Helicobacter, 15(5), 460–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00788.x

Marshall, B. J., & Warren, J. R. (1984). Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet (London, England), 1(8390), 1311–1315. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6

Mishra S. (2013). Is Helicobacter pylori good or bad?. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology, 32(3), 301–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-012-1773-9

Onsun N, Arda Ulusal H, Su O, Beycan I, Biyik Ozkaya D, Senocak M. Impact of Helicobacter pylori infection on severity of psoriasis and response to treatment. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:117–120

Testerman, T. L., & Morris, J. (2014). Beyond the stomach: an updated view of Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. World journal of gastroenterology, 20(36), 12781–12808. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12781