It’s time to meet your gut.

And we don’t just mean your stomach…. Before we delve into the world of microbes, let’s take a wee lesson to help us understand just how your gut works.

Digestion starts before food enters your mouth.

Imagine it’s nearly dinner time, the smell of spaghetti bolognese is wafting through the air (swap mince for lentils for added fibre with our recipe here!). You can see it bubbling away on the hob, you’ve tried a little mouthful and you’re thinking about grating a generous block of parmesan over it to serve. Here, you are experiencing the smell, sight, taste and thought of food – when this happens, your brain signals to your digestive tract that food is on it’s way and it’s time to release stomach acid and enzymes ready to digest the meal to come. This is called cephalic digestion.

Ever looked at a menu and noticed your stomach churning or that you’ve started to produce more saliva? That’s what we’re talking about here!

The anticipation is over, you’ve just taken a mouthful of your delicious bolognese. Yum. Delicious. Chew, chew, chew…

what happens now?

What happens in your mouth next is a fundamental part of digestion. Two crucial things happen here:

- Mechanical: the mechanical action of using your teeth to chew breaks down food into small particles, this increases the surface area that digestive enzymes have to work on.

- Chemical: glands in your mouth release saliva, which contains amylase to break down starch into maltose and dextrin (smaller carbohydrates). Saliva also helps to moisten your food to form a bolus (ball of food) ready to swallow.

are we nearly there yet?!

Not quite.

Your stomach, liver, pancreas and gallbladder are accessories organs, think of them as groupies to the band (the band being the gut!).

Back to the bolus of food. It travels down your oesophagus (not to be confused with your windpipe) and reaches your stomach – a muscular sac of an organ.

Here, there are other mechanical and chemical actions going on to help with the digestion of your meal and pathogens are warded off by stomach acid. The bolus becomes mixed up with a cocktail of stomach acid and enzymes forming a semi-liquid substance called chyme before making it’s way into the small intestine.

before we reach the small intestine, a little note about your liver, pancreas and gallbladder…

Your liver has a whole host of functions, including the production of bile (which is stored in your gallbladder), ready to be released when it’s needed. Bile is like washing up liquid, it emulsifies fat for absorption and contains cholesterol, bile acids, bilirubin (a by-product of broken-down red blood cells – the reason why your stools are brown). It is also responsible for eliminating waste (including toxins) from your body. There’s some really interesting research emerging about the relationship between bile and your gut microbes.

Your pancreas then secretes more digestive enzymes.

finally… we must be there?!

Not yet, the small intestine is a long tube split into three segments, the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Here, bile from the gallbladder and digestive enzymes from the pancreas work together to further digest your food.

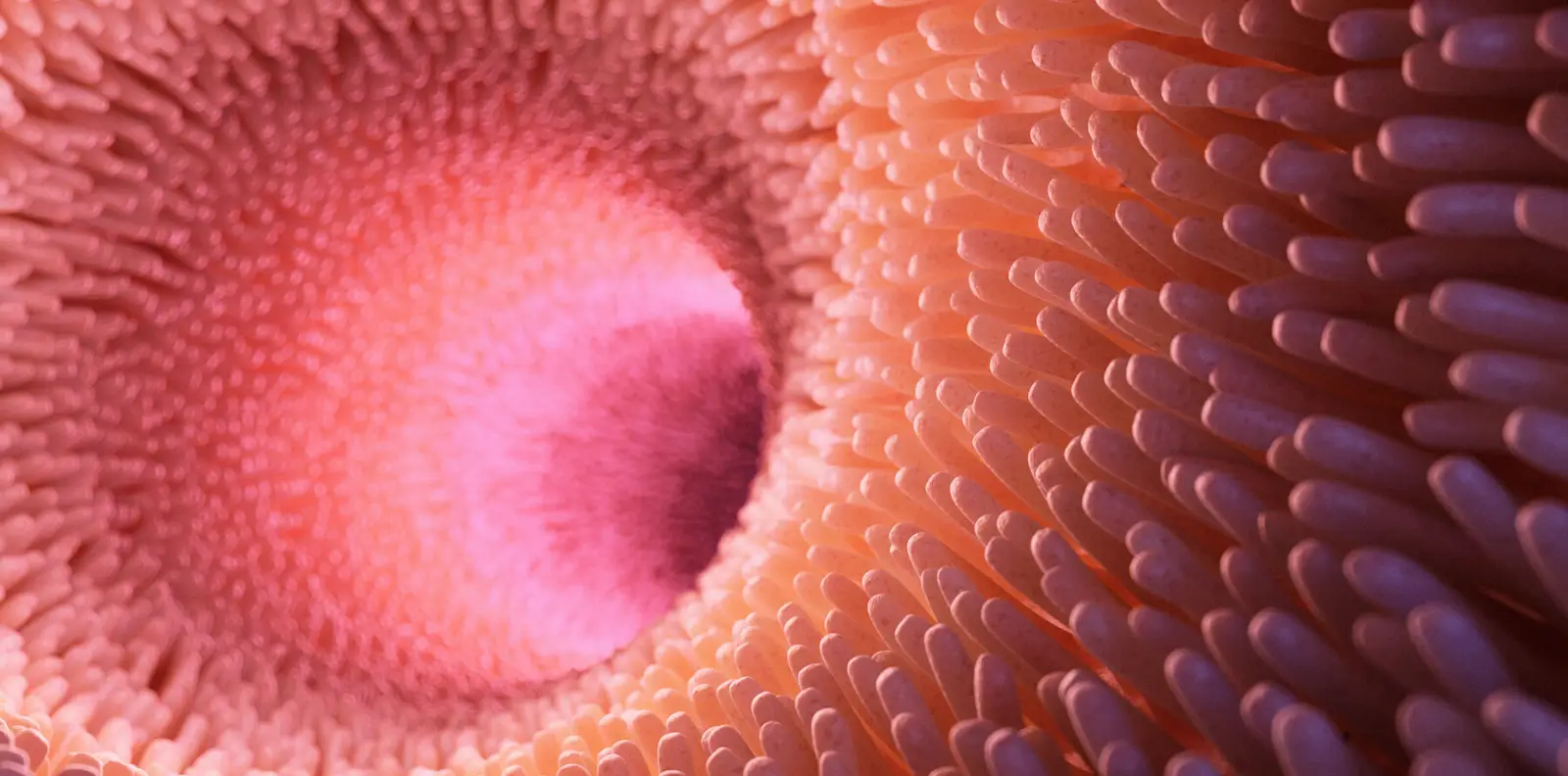

Muscles in your small intestine contract (peristalsis) and move your food along, this helps to mix it up with enzymes on the way. The small intestine is lined with tiny finger like folds (called villi) which increase the surface area for absorption. As the villi is only one cell thick, it is delicate and lots of things can impact it (more on this here). This process takes around 2-6 hours. Most nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream through the small intestine – this blood is then passed through the liver to be screened (like your nightclub bouncer).

almost there…

Any excess fluid travels to the large intestine where the body reabsorbs it (or it’s absorbed by fibre), increasing the bulk of your stool. This is why hydration is so important as it reduces the risk of constipation.

Undigested food and waste products are then carried by peristalsis (muscular contractions) along to the large intestine. Here’s where the magic happens, bacteria ferment undigested food, mostly fibre, and produce beneficial compounds such as short chain fatty acids and vitamins and have a good old sort out of waste. Clever little things!!!

The end

After all this hard work, your large intestine will make one mass movement to expel a stool, which is made up of essential waste products and bacteria. Ta da!

Get to know your gut

with our gut diary

Check out our gut diary© 2020 The Gut Stuff Limited. Not for redistribution or for commercial use – get in touch if you want to discuss our partner programme. If you’d like to use any of our infographics for personal use on your own social channels, we ask that you credit us @thegutstuff.